“I don’t promise to forget the mystery, but I know I’ll have a marvelous time.”

–Nancy Drew

Moonmist (1986)

Play and read along with game and source files (Obsessively Complete Infocom Catalog)

Packaging, copy protection, etc. (MoCAGH archive)

Packaging, copy protection, etc. (Infodoc archive)

Internet Archive query: “Moonmist”

HTML Invisiclues

Archived (z5) Invisiclues

Map (Infodoc archive)

Opening Crawl

Moonmist

Infocom interactive fiction - a mystery story

Copyright (c) 1986 by Infocom, Inc. All rights reserved.

Moonmist is a trademark of Infocom, Inc.

Release number 9 / Serial number 861022

You drove west from London all day in your new little British sports car. Now at last you've arrived in the storied land of Cornwall.

Dusk has fallen as you pull up in front of Tresyllian Castle. A ghostly full moon is rising, and a tall iron gate between two pillars bars the way into the courtyard.

What would you like to do?

>

Don’t Look Back

As 1986 drew to a close, Infocom’s last commercial hit, Leather Goddesses of Phobos, was in the rear-view mirror. The next and final three years of Infocom’s existence as what we would call today a “studio” would be marked by escalating commercial decline. Later works also failed to leave the cultural footprint of early Infocom games, excepting only Amy Briggs’s Plundered Hearts (1987).

Why had people moved on? One ready answer is that Infocom’s unique value proposition had become a hindrance. In the early 1980s, Infocom had successfully set itself apart from mechanically and narratively crude arcade games with advertisements like the memorable “WOULD YOU SHELL OUT $1000 TO MATCH WITS WITH THIS” full-page magazine pitch featuring a primitive graphical image of a stick figure. Infocom games, with sometimes lush descriptions and varied, humorous action responses, had found a way to marry mechanics and narrative in a way that Zork’s competitors could not.

1986 and 1987 were, more than half a decade later, a different epoch in the rapidly developing world of computer gaming. Infocom wasn’t competing with Adventure International or Namco’s PAC-MAN. They were competing with Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda. Origin Systems’s landmark Ultima IV: The Quest of the Avatar was released in 1985 with two feelie booklets and a cloth map, a handsome package that would have eclipsed many gray box releases. It is remembered today for its narrative reactivity, a quality that had once arguably been Infocom’s greatest strength.

How could Infocom have, in some alternate timeline, competed in this new era of mechanically and narratively complex graphical games?

Falling Short

One answer would be for Infocom to do more of what it did well. Even beloved games like Zork I, Enchanter, and Planetfall have in-game objects for which there are little to no descriptive text. Many default response messages lack customization. A practice of what I’d call “narrative propulsion” could be developed to create compelling, plot-driven stories, as we see this working well in 1987’s Plundered Hearts.

There were some rather impassible obstacles. For one, a perceived commercial need to make games compatible with the Commodore 64—a system with a large install base in the United States–imposed hard technical limitations on how much content an Infocom game could contain. While Infocom could add conveniences like “undo” and “oops” to its parser, it couldn’t make richer experiences for their target demographic.

It’s worth noting that Infocom did attempt to make larger games with their “Interactive Fiction Plus” line, but, even if they are among my favorites, I have to admit that A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity were from the beginning destined for significance rather than success. It’s also worth noting that, despite their sizes, neither AMFV or Trinity managed to fully characterize or describe their game worlds. Many locations in AMFV feature one sentence descriptions, and the endgame of Trinity is constructed from radically sparse text.

I think Infocom learned the wrong lesson from the commercial failures of Interactive Fiction Plus, as those new, larger works retained the rhetorical structures of 128K games. Design-wise, I think it would have been better to go deep rather than wide, if that makes any sense. I don’t think what Infocom games needed in 1986 were more rooms and more puzzles.

That isn’t to say that nobody enjoyed more for more’s sake, but I think early games hit a sweet spot in term of scope. How long does one want to play a single parser game? There would have been a question of return on purchase price in those days, but most consumers seemed to agree that relatively tiny Zork I was worth the money. I’m not sure whether focusing on text and plot would have generated sales, but Infocom’s approach to scaling up did not work commercially.

A Castle in the Clouds

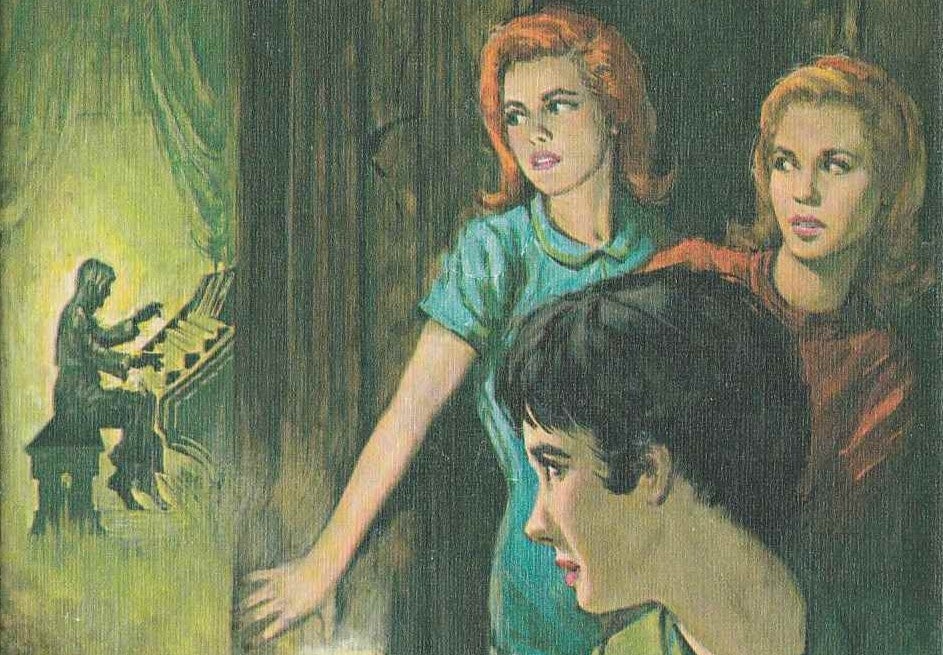

Perhaps no single game illuminates the exhausted rhetorical framework of 128K games more than Stu Galley’s and Jim Lawrence’s Moonmist, a title that sounds tremendously appealing in the abstract. Players are promised a Nancy Drew-style mystery in an atmospheric castle with a varied cast of personalities. Infocom’s marketing people seemed to appreciate the appeal of such an offering, as their The Status Line newsletter emphasized narrative intrigue and global reactivity:

You’ve spent the day driving southwest from London, from the small brick houses of the suburbs and the treeless plains of the South Downs to the Avon River and the picturesque villages of the Devon. Now, as evening draws near, you reach the storied land of Cornwall.

On either side, the moors stretch out, filled with heather and bogs. The fading light silhouettes craggy rocks on the horizon. At last you arrive at your destination: an ancient castle perched on the granite cliffs by the sea…

…Moonmist also responds differently to male and female players. (See the Leather Goddesses of Phobos article for another example of this fine feature.) When you arrive at the castle gate at the start of the game, you’re asked for your title and full name. You can take advantage of your elegant surroundings by calling yourself “Baron Wilhelm” rather than plain old “Mr. Bill.”

From your title, the program may deduce your gender and respond accordingly throughout the story. If you’re a woman, you have a gown to put on for dinner. A man’s suitcase will contain a dinner jacket. Lord Jack will kiss a woman’s hand. If you’re a man, he’ll shake yours. And there’s another guest who may flirt with you.

The promised atmosphere, narrative movement, and player customization are imperfectly realized, for reasons we will explore over the next two posts. For now, it is enough to say that the castle is large, empty and static.

Mixing It Up

I have yet to mention what many consider Moonmist’s most distinguishing feature: it includes four mysteries taking place in the same setting. At the game’s outset, the player can choose a color, and that choice will dictate which storyline plays out. This is a novel innovation that merits some appreciation. However, the consequence of this design choice is that we have yet again a title that forsakes depth for width. Instead of one trip through a mostly undescribed location, we are promised four.

>touch eye

The dragon's eye glows red. Evidently you just pushed a button. A voice comes from a hidden speaker. It says:

"Please announce yourself. State your title -- such as Lord or Lady, Sir or Dame, Mr. or Ms. -- and your first and last name."

>Ms. Fiona Lux

"Did you say your name is Ms. Fiona Lux?"

>yes

"And what is your favorite color, Ms. Lux?"

>Red

"Did you say your favorite color is red?"

>yes

"Jolly good! The spare bedroom is decorated in red! Please enter."

The red eye turns green, and the front gate creaks open.

It is fair, I think, to lay some of the blame for Moonmist’s utter lack of narrative urgency and mimetic vividness at the feet of Infocom’s self-imposed 128K ceiling, but as critics we must ask: why make a game that is, technically speaking, impossible to make well? Moonmist is not constructed within a framework that can feature a large and adequately-described castle with several people moving around in it, and it is quadruply incapable of telling four distinct stories.

In the course of my research, I encountered one internet conversant who characterized Moonmist as an “examining sim.” It is true that most gameplay involves examination as opposed to manipulation of objects. It is also true that examining things in Moonmist is usually unrewarding, as in-game descriptions do not assist in cultivating the sense of mystery promised by Infocom’s promotional materials. For instance, our protagonist has nothing to say about a “secret tape recorder.”

>examine recorder

You look over the secret tape recorder for a minute and find nothing suspicious -- for now.

Today, Moonmist is widely considered a lesser work. At the Interactive Fiction Database aggregator, it ranks just below Journey, a fact that might surprise the relatively few people who have played Journey. While aggregators do not capture such things, I imagine that Moonmist might rate very highly among games players wanted to like. Had it a narrower scope coupled with a deeper implementation, it might have better delivered on its promises. It is hard for me to play Moonmist without a pervasive sense of loss over what might have been.

Next

Next time, we will discuss the packaging and feelies that accompany Moonmist, paying special attention to the ways they might affect player experiences.

Leave a Reply